I carried my father in a sturdy cardboard box through the Nashville airport. He sat in my bag in the guest room at my friend’s house, and then in my suitcase at the Four Seasons in St. Louis. By the time I got to the airport for my flight back to Burlington, I knew to put him in his own bin going through security. The agents were respectful and even tender.

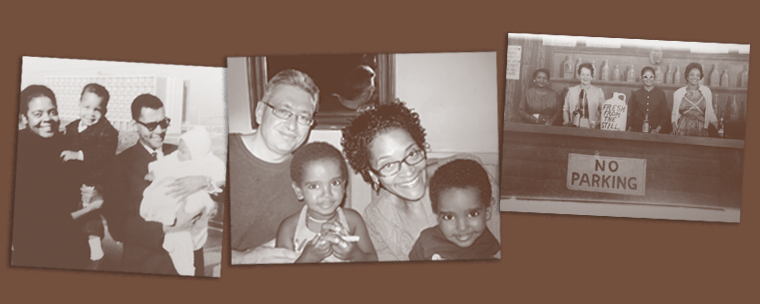

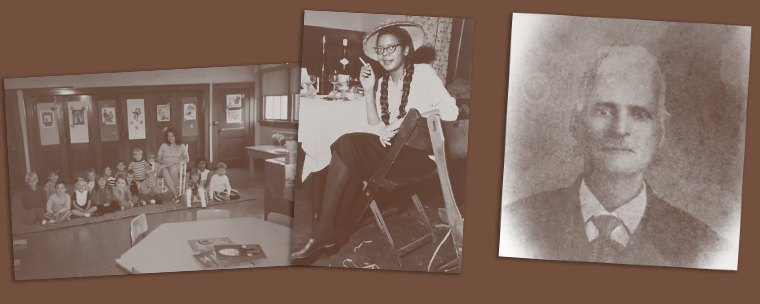

My father, my censor. How I miss him. I went down to Nashville to prepare him for the publication of Black is the Body over three years ago. He died the next morning, before I had a chance to give him the speech I had practiced. He wasn’t a reader, my father, but he was close to people who were, and I didn’t want him to encounter the family stories in the book through other parties.

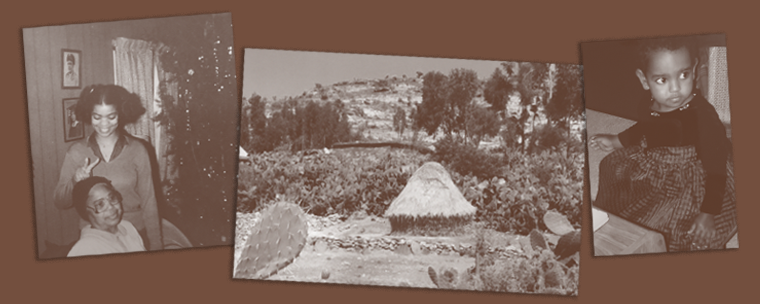

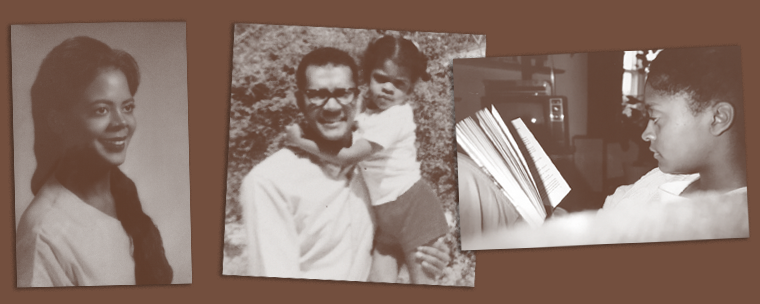

“Emily, don’t write this down,” I grew up hearing from him. “You should write all of this down,” my mother would say. In that intersection, in that can’t win for losing, I became a writer.

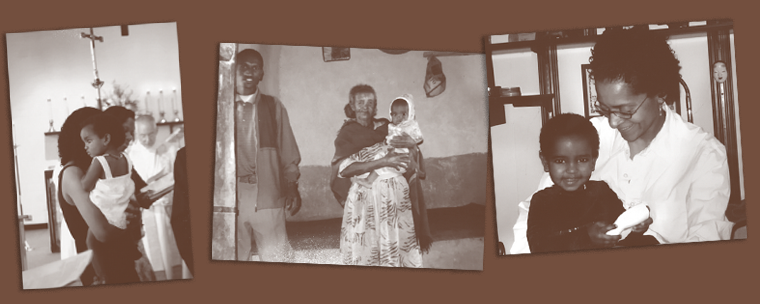

My father was a keeper of many secrets. I found evidence of my mother’s interior life in the things she left behind: letters, cards, poetry, scrapbooks. My father’s private life I can only imagine. There are people whose lives were shattered by his death; I talked to a few of them last week in Nashville, the first stop of my book tour. He was 83, but his life stopped mid-story. Who knows how it will end.