A Dingy White Mug: Holding on to my Nashville Childhood

Winter 2025

It’s the most valuable thing I own: a dingy white mug bearing the term Monistat, the brand name of an antifungal medication often used to treat yeast infections. The mug is at least fifty years old. Among its stylish, whimsical, and colorful neighbors in my kitchen cabinet, it sticks out like a sore thumb, like a fungal infection itself. Right now, it sits by my side.

The mug is made of hard plastic—a modern material—but it’s a relic from a long-ago era. A time when pharmaceutical companies arranged house calls at doctors’ offices to peddle their wares. My father was a doctor. His office and our home were full of detritus from these individuals, whose sales pitches included gifts of embossed coffee mugs, notepads, and pens. I picture the reps, a series of men, probably white, who made pilgrimages to my father’s practice, which was housed in a small white brick building on Buchanan Street in North Nashville—what used to be Black Nashville, located squarely on the “wrong” side of town, according to the American system of redlining.

My Name Is Emily

Spring 2024

My name is Emily. Like every story that defines the course of a life, the story of my name began long before I was born. Emily was the name of my paternal grandmother. I never really knew her, though I can recall in precise detail the first time I met her. My father had taken my younger brother and me back to the country of his birth—the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago—so that we could be presented to his family, something many immigrants of his generation did. I was three years old. I remember my grandmother Emily as an old woman with deep-brown skin, dressed all in black, like a creature from another world, the Old World of my father’s childhood. And just like his childhood, my father’s mother was a mystery to me. Even to a three-year-old, she seemed fully contained, dense, full of secrets rich and deep, like a grave.

It All Begins in Love

Winter 2024

Among the photographs that make up “A Long Arc,” an exhibition documenting the American South from the 1840s to the present, is James Van Der Zee’s powerful depiction of a classroom in Phoebus, Virginia. The photo, dating to 1907, represents the Du Boisian dream that I, like so many generations of Black Americans, have built my life around. When I first arrived to teach English at the University of Vermont, in 2001, I kept an image taped to my computer, a picture of an old Black woman sitting in a chair reading while a young Black woman stands behind her, pointing to the book, presumably helping the older woman make her way through the pages. I kept it there to remind myself that my purpose was something larger than my own needs and desires. It was helpful in those lonely, early days, when I was as uncertain of the life I had chosen as I was of the state in which I had chosen to live it. Below the image, for a caption, I typed out and pasted a line from the prologue of Invisible Man: “Old woman, what is this freedom you love so well?”

What Is Touching

Issue 118

I am standing in my kitchen, trying to remember the first time we touched. I think it was at the restaurant in Savannah. The room was loud in a way that I like: thick bursts of conversation far enough away, but the group of us cocooned inside our own little planet, united by the soft tissue of affection and curiosity. Ostrich was on the menu. We were six random people in town for a seminar sitting close around a low wooden table talking about the strangest things we’ve ever eaten. There was some competition over whose appetites were most pitiless. A discussion of unusual food quickly degenerated into talk of murder. Devastating scenes of bloodshed were laid out like garish hors d’oeuvres. We learned how a pig is gutted, the deliberate and slow art of draining life from a being against its will. We heard stories of bloody deer splayed out in the back of trucks and how they got there; decapitated snakes; poultry choked to death by bare hands (that was my contribution). Bloodthirsty tales of stalking and hunting executed as solemn, sacred preludes to holiday meals. You and I both chuckled, talked, and kept eating through the remembered massacres, but as you sat next to me, I was aware that you were receiving these stories with a gravity that was not represented in your big laugh and open manner. Maybe it’s because we were both Black, but when our knees touched, I felt it was because of a shared understanding of what it meant to feel like prey.

This Part of Our Lives is Over: Sending my daughter to Japan

June 12, 2023

My daughter Giulia is going to Japan. We all get up before the sun rises to take her to the airport—me, my husband John, and her twin (and sparring partner) Isabella. Even our dog Rosie, who is really Giulia’s dog. Giulia had texted me from her bedroom at 3:00 a.m.: Are you awake yet. Yes! I responded. Not: I haven’t been able to sleep! Which was the truth but not a truth that will serve Giulia this morning. “Calm, calm, calm” has been my mantra over the last several days, as the preparations to send Giulia abroad have gathered speed and intensity. My daughters are juniors in high school. They have recently turned seventeen.

We move carefully around one another, gingerly trying out the steps of this new choreography, which we are composing in real time. Giulia has never been on a plane by herself, much less traveled all the way to Japan. What does Giulia need? One thing she always needs is quiet. We use words sparingly, perhaps out of deference to this fact as much as to the general absence of sound and sun at this early hour. The only light is artificial. By the time we drop Giulia off, the sun will not have risen. We will part with her under the same dark cover that accompanies us to the airport.

A genius of the South. An embarrassment to the race. Singular American author; craven literary con artist. She was a loving champion of Black vernacular; she was a mundane writer of facile prose. A misunderstood cultural icon; a perfect darkie. Survivor. Victim. Trickster, liar. These are the various lenses through which generations of critics, fans, scholars, and detractors have assessed the life of Zora Neale Hurston. All of these perspectives are accurate, and not one of them is true. But these various portals lead to two important questions: Who was Zora Neale Hurston really? And how did such an exceptional person—the most famous Black woman artist of her time—wind up penniless and buried in an unmarked grave?

All life writing is an attempt to fairly and fully assess the meaning of a life. The job of the biographer is to present a comprehensive character, a known person. This is the goal. But the true story unfolds along the way; there is no exact point of arrival. Just as it is impossible to capture the full mystery of the ocean in a snapshot, there is no single lens that can contain the totality of a human life. Biography raises more questions than it answers. Among them is: How do we come to know anyone at all?

The Womack Originals

July 6, 2021

Saint Heron presents “The Womack Originals”, an intimate profile on the story of the legendary Linda and Cecil Womack, as told by their three daughters Zekuumba (BG), Zeimani, and Kucha (KC) Zekkariyas on the journey into raising and educating their seven children in over eight countries, and four continents, while creating new family structures- spiritually, culturally and musically.

Known creatively as Womack & Womack, the Saint Heron dossier is a legacy story paying homage to Linda and Cecil Womack’s unique and inspiring journey. The dossier, penned by the award-winning author of “Black is the Body” Emily Bernard, paints an intimate portrait of a radical family dynamic based on Emily’s interviews with the duo’s daughters.

Read on the Saint Heron Dossier: WWW.SAINTHERON.COM

Audre Lorde Broke the Silence

Mar 25, 2021

“Is it possible to be a black lesbian writer and live to tell about it?” asked budding writer and scholar Barbara Smith at the 1976 convention of the Modern Language Association. Among those in attendance was Audre Lorde, an established poet, whose first collection, The First Cities, was published in 1968. The question, largely rhetorical, was addressed to the entire assembly, but Lorde took it personally. “I thought, ‘Oh boy, I’ve got to start writing some of that stuff down. She needs to know that, yes, it is possible.’”

A self-described Black lesbian mother warrior poet, Audre Lorde lived a life of possibility. To her readers, colleagues, and admirers, she offered a radical and liberating vision of the world in her work. Eminently faithful to the tenet that the personal is political, she wrote fearlessly from the landscape of her most intimate self. Lorde treated her body—the range of her corporeal needs, fears, and desires—as a resource of political and creative information, a platform from which she communicated her worldview. She was unique in her determination to speak and write without shame, but at the same time wholly representative, embodying the complexities of a contemporary radical Black feminist identity.

‘Adoption has been a journey from ignorance to enlightenment’

Feb 7, 2021

I assumed I would conceive naturally when John and I decided to start a family. I didn’t. We turned to fertility drugs with ambivalence. Reports of the mood swings the drugs sometimes caused worried me. I had only gone through one round when I broke a wooden dish-drying rack over John’s head. I don’t remember what he said, but I’m sure it was something I’d otherwise have considered innocuous. Instead, a growling, uncontrollable rage emerged from nowhere and then overcame me like an emotional tsunami. We decided the drugs weren’t for us.

I had gone along with fertility treatments for the same reason I went along with other non-decisions I’ve made in my life, like having an enormous wedding, because people whom I loved wanted it for me. I thought I was supposed to want it, just like I was supposed to want to get pregnant by any means. Yet I cried genuine tears when, month after month, I was unable to conceive. I felt like a failure.

From the Stranger in Me to the Stranger in You

Issue 106

In the Spring of 2019, I gave a reading in southern California. My book Black Is the Body had been out in the world for a few months, and I had traveled to bookstores and libraries up and down the East Coast to promote it. In California, I would be meeting with readers and also several faculty members in the humanities. I had no doubt that it would go smoothly.

After all, I would be among teachers, my tribe. That night, I stood at a lectern, read from Black Is the Body, and answered questions. When the event was over, a few readers came to the stage to share stories of their own and get their books signed. Out of the corner of my eye, I watched my host gather the faculty who would be joining us for dinner.

Caste by Isabel Wilkerson Is a Trailblazing Work on the Birth of Inequality

August 4, 2020

The Warmth of Other Suns, the first book by Pulitzer Prize–winning writer Isabel Wilkerson, offered an epic narrative portrait of the Great Migration.

In her magnificent latest, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, Wilkerson deepens and extends her examination of the inception and consequences of American racism, finding direct connections to the outcastes of India and the horrors of the Third Reich.

The Purpose of a House

June 25, 2020

My friend Maurice Berger, a writer, art curator, and social-justice advocate, died in the first stages of the pandemic, just as stay-at-home orders spread, like the virus itself, throughout the United States. I was already in an active struggle—not quite a losing battle but certainly not a winning one—with fear and anxiety. Maurice’s death knocked me over. I took to the darkness, like a drug, sleeping with the shades drawn. “I have no fight in me,” I told my husband when I was awake and upright, scaring him half to death.

I Can’t Sleep: After days of witnessing racial violence, respite is no longer a given

Summer 2020

It’s 1 a.m. I lie in my bed in the dark, my heart beating fast. I knew this would be a hard night; I got to bed by midnight, but the interior stream of words never stopped. I took drugs—both pharmaceutical and herbal (this is Vermont)—hoping they would quiet the flow and allow me to sleep. They didn’t work; the stream rushed into a river. Phrases and sentences propel me upright. I turn on the light and scratch them out quickly, trying not to wake John, my husband, who sleeps soundly beside me.

I turn the light back off. Can I sleep now? I plead with the darkness. No. I drag myself out of bed and down two flights of stairs to the guest bedroom. I am afraid to be alone with my thoughts, but desperation overwhelms my fear.

What is this word? I am three years old and perched on my mother’s hip. We are in the kitchen; my mother mans the stove. My legs hang around her waist, unanchored. I know she will hold me; she won’t let me fall.

I am holding a book. “What is this word? This word?” My finger moves along the page. Sometimes I peer into the pots on the stove, getting so close that my mother is forced to stop stirring. She sinks us into her seat at the head of the table, opposite my father’s. It’s just the two of us today, my mother and me, which will forever be the way I like it. I did not know it at the time, would not know it for years, but every morning she sat in this chair and worked on drafts of her poems.

Autobiography of an Ex-Black Man: Thomas Chatterton Williams loses his race

December 2019

“I’m the happiest I’ve ever been!” declares Wanda Sykes in her 2016 Epix special, What Happened . . . Ms. Sykes? As one of her fans, I was glad to hear it. As a member of a racially and culturally mixed family, I was particularly charmed to learn the circumstances of Sykes’s joy. For ten years, Wanda Sykes has been a mother. Her wife, Alex Niedbalski, gave birth to twins Olivia and Lucas in 2009. “My kids are white white, you know? I mean blond hair, blue eyes. I’m talking Frozen,” says Sykes. “Never in a million years would I have imagined myself in this situation.

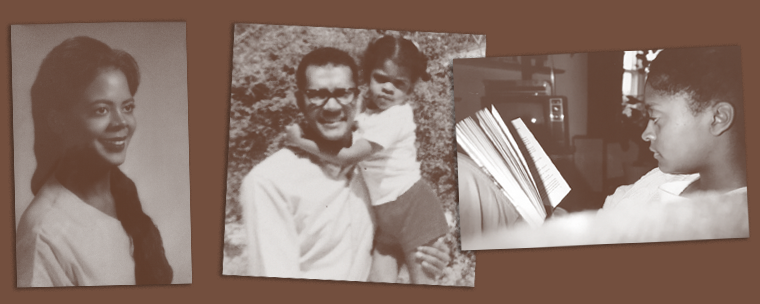

Black is the Body Author Emily Bernard on Why She Forgave Her Father's Mistress

October 2019

“I don’t understand why he would buy it for her.” My mother sat at the kitchen table while my brothers and I orbited her chair. She kept track of our family finances and had come across a curious receipt. My father had purchased a plane ticket for one of his patients, Jeanette Currie. “It doesn’t make any sense,” my mother said, as much to herself as to us.

“You worry too much, Mom!” I teased. My mother was a fretful person, supervisor of details and predictor of all that could go wrong. I just wanted to change the subject.

It was December 1988 at my parents’ home in Nashville. I was on winter break from college, and my older brother, James, was back from New York to spend Christmas with us. My younger brother, Warren, was a high school senior. As siblings, we had our differences, but we always snapped together like magnets around our mother, whom we uniformly adored. I wanted her to relax and join our reunion, cracking inside jokes the four of us had honed over many years. I was sure my father would eventually explain the ticket.

What I didn’t know then was that for several years he had been building a secret life, with Jeanette Currie at its center.

How a Group of Healers In Peru Helped Me Discover A Miracle—Within Myself

March 2019

Broccoli. That’s the word that comes to mind as my plane descends into Iquitos, Peru. From my window, the Amazon jungle appears to be made up of countless bunches of flowering broccoli heads. I have never seen anything like it—neither the broccoli trees, nor the snaking tributaries of water that weave between them. Looking back, I think my brain was trying to make sense of the landscape as I landed in a part of the world where I had never been. But I have not come for the scenery. I have come in search of a miracle.

What is my life’s purpose? How do I break through this crippling self-doubt? Am I meant to have children? Will I ever learn to give and receive love? These are the questions I often ask myself, but I have no clue how or if I will discover the answers. As I deplane, I am suddenly startled by the more practical things I don’t know, such as the local currency or where I’m going to sleep tonight.

I was 16 when I first read Toni Morrison. A friend of my parents gave me Morrison’s earliest novel, The Bluest Eye, the searing and tender story of Pecola Breedlove, an 11-year-old Black girl who yearns for blue eyes, which she thinks would make her beautiful. Pecola burrowed her way inside me and touched my own fears and insecurities as an African American female growing up in the South, but when I examined the author photo on the back cover, I saw that Pecola’s creator was a woman about as old as my mother and father. How was it, I wondered, that this nearly middle-aged stranger could see and understand my secret self so clearly? What magic powers did she have?

But What Will Your Daughters think?

January 2019

“I wonder what your daughters will think?” asks Annette, the wife of a fiction writer. We are in the auditorium at a book festival, and I have just read a short story based on an actual weird and fraught relationship I had with a high school teacher when I was a teenager. Annette waits; she really wants to know.

“I guess we’ll find out,” I say and laugh. My twin daughters are seven years old.

The story is called “What Happens Next?” It is autobiographical and it is about sex. Not intercourse per se, but the mysterious world of adolescent female desire. The fictional me in “What Happens Next?” is full of shame. She is a girl who is interested in sex, but not in the way she thinks she is supposed to be.

People Like Me

December 2018

“Home is longevity,” Ellie says when I ask what the word means to her. Ellie and I grew up together in Nashville. During our high school years, we slipped each other notes every day in class and spent hours every night on the phone. On weekends, we practiced dance moves side by side in front of mirrors in the rec room of my house. Never, during those years, could I have conceived of a life in which she would not be a constant presence.

Ellie teaches high school in St. Louis, where she has lived for most of her adult life. I have lived in Vermont for seventeen years, since John and I arrived to assume faculty positions at the university. Seventeen years and I still do not call Vermont home. Maybe I never will.

Witnesses for the Future

June 2018

“You have seen how a man was made a slave,” Frederick Douglass wrote in his 1845 autobiography, the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. “You shall see how a slave was made a man.” These words herald the moment when Douglass masters his master, the sadistic overseer and “negro-breaker,” Edward Covey, seizing him by the throat. More remarkable than Douglass’s physical prowess was the fact that he lived to write about this at all: In addition to the beatings and other miseries, Douglass endured severe cold that left gashes in his feet pronounced enough to cradle his pen. “Written by himself” is Douglass’s subtitle, a phrase that resounds throughout early African American autobiographical writing. Douglass’s books, along with photographs of the author, portrayed a man who was fully self-composed. The story was the self.

Interstates

Spring 2017

John, my parents, and I are heading south on Interstate 55 from Nashville to Hazlehurst, Mississippi. He is driving; my father rides shotgun. I sit in the back with my mother, holding my breath. The entire car is silent, all four of us as still as stones.

“We have to pull over,” John says.

It is a midmorning in July. I try to focus on passing cars.

“There’s a gas station a few miles up,” my father says evenly. He shifts in his seat.

The front left tire is flat.

The Value of Clarity

August 2016

A few years ago, I was invited to give a job talk at a Midwestern university. I am content enough at my current institution not to have applied for another job in 15 years. But I was curious. So, even though it is wrong to go on dates when you are married, I went.

The visit was largely unpleasant and entirely confusing. Few people seemed to be interested in my work. One prominent member of the faculty made no attempt to hide his disdain for scholars who write for mainstream audiences. “Why should my writing be clear?” he blustered. “Scientistsaren’t expected to be clear.” Dude, you are not Jonas Salk, was among the rejoinders that I came up with on the plane ride home.

Several years ago, Ta-Nehisi Coates took his son, not yet 5, to see a movie on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. As his son made his way off the escalator, a white woman pushed him and said, “Come on!” Chaos ensued. There was a black parent’s rage and a white man’s threat to have the black parent arrested. Coates narrates the incident in cool, steady prose. Ultimately, he writes of the regret he carries: “In seeking to defend you I was, in fact, endangering you.”

Useful

March 2014

Many years ago I was sitting with a jazz musician in an auditorium when a song by Norah Jones came on the loudspeaker. He asked me what I thought of her music. I told him I liked it. He shook his head. “I can’t use it,” he said.

Ever since then I have kept his words in the forefront of my mind whenever I begin an essay. They get me through drafts when sentences that felt like evidence of genius the night before reveal themselves to be crimes against paper in the light of day. And they get me back on track at the end of long dry spells, “who the hell do you think you are” stretches when I wonder what I could possibly have to contribute to a conversation I desperately want to join.

Scar Tissue

Autumn 2011

I have been telling this story for years, but telling is a different animal from writing. In the telling and retelling, I have shaped a version of it, one that fits neatly in my hand, something to pull out of my pocket at will, to display, and to tuck away when I’m ready, like a shell or a stone or a molded piece of clay. The story that I have honed over the years is as neat as my scar; it is smooth, and tender, and conceals more than it reveals.

Fired

Winter 2007

On a Saturday morning at 10:00 a.m., Beverly and I planned a trip to Long Island, just us girls, to celebrate my upcoming marriage. By that evening, Beverly and I were no longer friends. But I didn’t know that yet. At 7:00 p.m. I was sure there had been some mistake, some misunderstanding, some bizarre but absolutely explainable crossing of wires—she hadn’t gotten my messages, she had fallen into bed with some new boy, she had been kidnapped. I would continue to turn various scenarios over in my head for the next several months until finally I had to accept the truth—I had been fired.