BLACK IS THE BODY named a Best Book of 2019 by Kirkus Reviews & NPR as well as one of Maureen Corrigan’s 10 “Unputdownable” Reads!

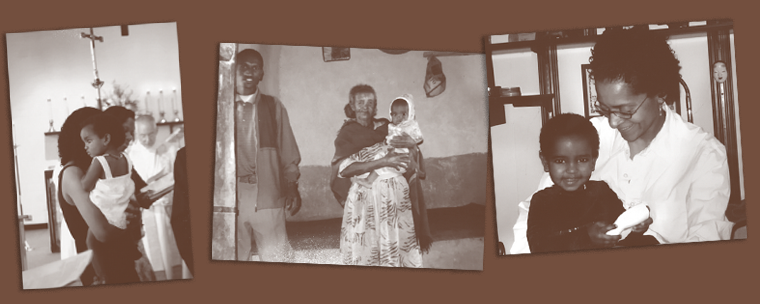

Emily Bernard was born and raised in Nashville, Tennessee. She holds a B. A. and Ph. D. in American Studies from Yale University. Her work has appeared in TLS, The American Scholar, The New Republic, The New Yorker, The Yale Review, Harper’s, O the Oprah Magazine, the Boston Globe Magazine, Creative Nonfiction, Green Mountains Review, Oxford American, and Ploughshares. Her essays have been reprinted in Best American Essays, Best African American Essays, and Best of Creative Nonfiction. Her first book, Remember Me to Harlem: The Letters of Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten, was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. Her most recent book, Black is the Body: Stories from My Grandmother’s Time, My Mother’s Time, and Mine, won the 2020 LA Times Isherwood Prize for Autobiographical Prose. She has received fellowships and grants from Yale University, Harvard University, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Vermont Arts Council, the Vermont Studio Center, and The MacDowell Colony. A contributing editor at The American Scholar, Emily is the Julian Lindsay Green and Gold Professor of English at the University of Vermont. A 2020 Andrew Carnegie Fellow, she lives in South Burlington, Vermont with her husband John Gennari and their twin daughters.

Carnegie Corporation of New York Names 27 Winners of Andrew Carnegie Fellowships

“Carnegie Corporation of New York congratulates the 2020 class of 27 Andrew Carnegie Fellows who were announced today. Each will receive $200,000 in philanthropic support for high-caliber scholarly research in the humanities and social sciences that addresses important and enduring issues confronting our society.”

The Observer: ‘Adoption has been a journey from ignorance to enlightenment’

“I assumed I would conceive naturally when John and I decided to start a family. I didn’t. We turned to fertility drugs with ambivalence. Reports of the mood swings the drugs sometimes caused worried me. I had only gone through one round when I broke a wooden dish-drying rack over John’s head. I don’t remember what he said, but I’m sure it was something I’d otherwise have considered innocuous. Instead, a growling, uncontrollable rage emerged from nowhere and then overcame me like an emotional tsunami. We decided the drugs weren’t for us.”

I had gone along with fertility treatments for the same reason I went along with other non-decisions I’ve made in my life, like having an enormous wedding, because people whom I loved wanted it for me. I thought I was supposed to want it, just like I was supposed to want to get pregnant by any means. Yet I cried genuine tears when, month after month, I was unable to conceive. I felt like a failure.